THE WILLCOX

& GIBBS SEWING MACHINE COMPANY

AND THE WEST VIRGINIA CONNECTION

My interest in this machine

|

I

have always had an eye for beautiful machines. Early sewing

machines were often considered the most beautiful of all the machines

man had made up to that point. Only early guns and clocks

rivaled sewing machines for beauty.

I was an upholsterer and had seen many old

machines, but never really thought of owning one just for the

heck of it. But this one was

different.

First however,

I came home and did some research on it. As I soon

learned, the company had quite a history which only added to

my interest in owning it. The following day I bought it. Turns

out that my machine is museum quality. There are very few left in

this condition and I have yet to see one as good as mine.

|

I have every part made for this machine and then some.

If

you've ever opened a big bag of flour, pet food, salt, litter, or any

of a hundred other items that come in a bag with a sewn top,

you've used the process that James Gibbs

invented:

The Chain Stitch Sewing Machine. |

|

HERE'S THE WV CONNECTION

ON THE DIVIDING LINE between Augusta and Rockbridge counties Virginia

lies Walnut Grove, home of Cyrus Hall McCormick, inventor of

the reaper. McCormick's invention assured him of lasting fame and

recognition, but in a nearby village lived another inventor whose

accomplishments were overshadowed by his competitors and whose work is

little remembered outside his native Rockbridge county.

James Edward Allen Gibbs invented a sewing machine and founded a company to

market it which is still in existence today. He is the only inventor

outside of the New England states to produce a sewing machine. Yet

Elias Howe and Isaac Singer are the names usually associated with the

history of the early sewing machine and few have ever heard of James

Edward Allen Gibbs.

From 1845 until 1856 when he patented his sewing

machine, Gibbs worked at various occupations and in several different

locations. For awhile he rented a building and operated a carding mill

( Before wool can be spun into yarn for knitting or weaving into cloth,

it first must be brushed, or carded ) in Lexington Virginia, but

finding himself debt ridden, he left there in the early 1850s and went

to Huntersville in Pocahontas County, now in West Virginia.

(Huntersville still exists and is only 6 miles East of Marlington)

Gibbs became a partner in another carding business, but sold his

interest when that business, too, proved to be unsuccessful.

After leaving the carding business, Gibbs engaged

in a variety of activities. He joined a surveying team in Randolph

County, also in present-day West Virginia. On a surveying expedition

he suffered a serious injury when, while cutting down a small pine

tree, his ax slipped, cutting through his right knee cap. His

companions took him to the home of Alexander Logan at Mingo

Flat (the town is still there half way between Snowshoe and

Valley Head WV) where for six months the Logan family, and especially

William Logan, nursed him through to his recovery.

(After

the Civil War, when fortune had favored Gibbs and taken everything from

William Logan, Gibbs aided Logan in establishing a store at Midway,

Virginia.) The knee injury, however, prevented

Gibbs from resuming his career as a surveyor and he became a carpenter

and a millwright. In the winter of 1851-52, he built a grist and

sawmill for Colonel Samuel Given in Nicholas County.

While

engaged in this project, he met Colonel Given's daughter, Catherine.

The dark-haired young man with the big nose and sharp blue eyes could

not have been called handsome, but he had a strong personality, and a

social nature that Catherine must have found charming for they were

married on August 25, 1852.

Refusing his father-in-law's offer of 500 acres of

land and the equipment to start a farm, Gibbs returned with his wife to

Pocahontas County where he continued to work as a carpenter.

Elias Howe, William O. Grover, William E. Baker,

Isaac Singer and others, patented sewing machines in the early 1850s

and revolutionized the clothing industry. In 1855, Gibbs saw a woodcut

of a Grover and Baker sewing machine in a newspaper advertisement. It

was the first image of these new contraptions that he had seen and

there was little to show him how it worked.

All that was shown

in the woodcut was the top half of the machine. Nothing indicated that

more than one thread was used to form the stitch or indeed how the

stitches were made. Gibbs decided that only one thread was used and

since his curiosity was aroused, he formed in his mind a method for

producing a single thread stitch. He later described the experience,

saying:

"As

I was then living in a very out-of-the-way place, far from railroads

and public conveyances of all kinds, modern improvements seldom reached

our locality, and not being likely to have my curiosity satisfied

otherwise, I set to work to see what I could learn from the woodcut,

which was not accompanied by any description.

Gibbs's

curiosity had been satisfied and he did not immediately pursue the

matter because he did not realize the significance of his invention.

However, in January 1856, when he was visiting his father in Rockbridge

County, he happened to enter a tailor's shop and there saw a Singer

sewing machine. Although Gibbs was impressed by the machine, he thought

that it was "entirely too heavy, complicated, and cumbersome, and the

price exorbitant". He remembered his own simpler invention and decided

to work seriously on a less-expensive sewing machine.

James

E. A. Gibbs was hampered in his attempt to perfect his sewing machine

because he had to support his growing family and could only work on the

invention at night and during inclement weather. In addition, he lacked

proper tools and sufficient materials.

After months of

effort, Gibbs succeeded in making, with his pocket knife, a crude

wooden model. He made the needles for the machine himself and,

according to his daughter, used the flexible root of mountain ivy to

fashion the revolving looper which was the key to his invention. By

April 1856, it was almost ready and Gibbs reportedly sold a half

interest to John H. Ruckman, local owner of a sawmill, in order to pay

to have the machine patented.

Gibbs could whittle

and invent, but he realized that he could not market his machine alone.

With his letters of patent in his pocket, he went to Philadelphia.

"I

was in Philadelphia in 1857", he later wrote, "selling the first of my

first two inventions in the office of Emery, Houghton and Company, when

James Willcox came in. He remarked that he was a dealer in new notions

and inventions, and he asked me to come to his little shop in Masonic

Hall and build a model of my machine".

Gibbs

worked with Willcox's son Charles to build a patent model and on June

2, 1857, he was awarded patent number 17,427 on his machine. As a

result of the successful patenting of the machine, Willcox and Gibbs

soon formed a partnership. In 1858, Willcox engaged the firm of J. R.

Brown and Sharpe of Providence, Rhode Island, to produce the sewing

machines and the first ones were manufactured in November 1858. To

market their machine, Willcox and Gibbs opened an office at 658

Broadway in New York City the following year.

Not

only had Gibbs successfully designed a simpler machine than the Singer

model he had seen in Rockbridge County in January 1856, but his new

sewing machine was also much less expensive. The Willcox and Gibbs

machine, sold on a simple iron-frame stand, cost $50 at the end of the

1850s compared to a cost of $100 for the machines produced by Wheeler

and Wilson, Grover and Baker, and Singer.

|

Here

is a very abbreviated version of the Willcox & Gibbs

story.

|

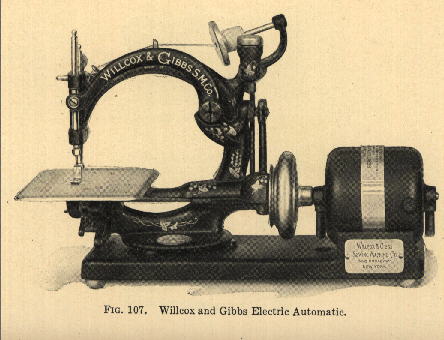

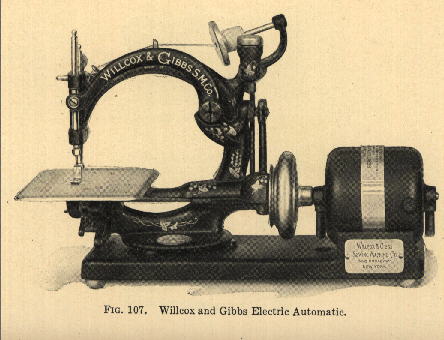

GETTING

THE first Willcox and Gibbs machine from drawing board to the shop

counter was an adventure beset with more engineering problems than

most. Willcox, who was in charge of production, approached

the

Providence, Rhode Island, company of Brown and Sharpe who were at that

time makers of clocks, watches and measuring instruments, and asked if

it would be interested in producing the new sewing machine. The project

was turned over to one very young man, Henry LeLand, who later would

design and build the Cadillic and Lincoln automobiles.

Work

began in March 1858 when the first drawings were made and soon the

local New England Bull Company was busy on the frame castings. When the

figures were finally totaled, it was found that Brown and Sharpe had

spent 10 times its original budget just on the tooling for the machines.

But

in October 1858 it all came together. Sharpe wrote to Willcox saying

that the first 50 machines were on the final assembly benches and that

the firm was now able to produce at the rate of 5000 per year.

Fortunately, for all concerned, the machine was an instant success, and

the small tool room quickly became a factory, continuing to make the

W&G machines well into the 1970s. Brown and Sharpe continued with its instrument

business and developed a world-famous name for selling specialized

machine tools to other sewing-machine manufacturers.

|

Early Willcox & Gibbs

sewing machine

CIVIL

WAR IN WEST VIRGINIA

|

In 1860, James E A Gibbs was 30 years old and had

attained a modest degree of financial success. The Pocahontas County

census of that year listed his occupation as a machinist and valued his

real estate at $2,000, while his personal estate was worth $15,647.

Immediately after the news of the firing on Fort

Sumter, in April, 1861, he left Providence to live on the farm he had

purchased in Pocahontas County. Matters political had a keen interest

for Gibbs. He was a Democrat, and in the state campaign of

1855 he had made speeches in Pocahontas in favor of Henry A. Wise as a

candidate for governor. For the Lewisburg Chronicle he wrote a parody

in ridicule of the American, or Know Nothing, party. In the present

crisis his sympathies were with the extreme Southern program. He went

on the stump in advocacy of secession, and went to Richmond to get arms

and uniforms for the first company of cavalry. These

uniforms were sewed on two of his machines. Old guns and pistols were

repaired in his shop. He went out with the Pocahontas cavalry, but his

constitution was never strong, and in three weeks he was sent home, ill

with typhoid- pneumonia. The advance of a Federal army caused Gibbs to

return as a refugee to his native county and neighborhood. He bought

the farm near Raphine which became the nucleus of an extensive

possession. In Rockbridge he was assigned to the ordnance service to

superintend the making of saltpeter. When General Hunter approached, he

was ordered out with his twenty men, and they fought in the battle of

Piedmont. ***See battle below***

After

the war, Gibbs decided to go to New York to discover if anything

remained of his sewing-machine business. Borrowing a broadcloth suit

from a brother-in-law, he left Virginia in June 1865. His daughter,

Ethel, recalled later that her father was followed from Jersey City to

658 Broadway in New York by a Northern detective who thought he was a

man named "Gibbs from Louisiana, who had invented the famous mortar

used by the Confederate Army". When Gibbs entered his old office, the

detective evidently realized he had the wrong man. James and Charles H.

Willcox greeted Gibbs with open arms and told him that they had

deposited $10,000 in the bank to his credit. The two Willcox men had

not made it public that the credit was for a Confederate because the

money would have been confiscated.

The inventor was now, at the age of thirty-six, and

for the first time in his life, a dweller on Easy Street. In 1880, for example, Gibbs enjoyed a

combined income of about $10,550 including over $9,000 in bonds and

notes. He refused to become an officer of the Willcox and Gibbs company

when it was incorporated in New York as a stock company in 1866. He

preferred, as did his wife, to live in the two-story brick home he had

built on his farm.

Christened

Raphine Hall, from the Greek word raphis, meaning needle, the house was

large and comfortable and included a wing where Gibbs worked on his old

inventions as well as new ones. In 1883, he gave a right of way to the

Baltimore and Ohio Railroad to build its line and the land for the

station, which he also named Raphine.

Gibbs

continued to work with his company until about 1886. During that time

he traveled widely, especially in Europe, to promote the sales of the

Willcox and Gibbs sewing machines.

|

FINAL NOTE:

|

Among

those who worked on Willcox and Gibbs machines at the Brown and Sharpe

factory was one Henry Leland who was in charge of the sewing-machine

department from 1878 until 1890. Leland went on to devote his skills that he had

learned on sewing machines to forming the prestigious Cadillac Car

Company .

|

|

Henry

Martyn Leland (February

16, 1843 – March 26, 1932) was a machinist,

inventor, engineer and automotive entrepreneur who founded the two

premier American luxury marques,

Cadillac and Lincoln. He, as a young man, was in charge of

manufacture of the Gibbs sewing machine.

|

| He

was born in Barton, Vermont and learned engineering and precision

machining in the Brown & Sharpe plant at Providence, Rhode

Island,.

He

subsequently worked in the firearms industry, including at Colt. These

experiences in toolmaking, metrology, and manufacturing steeped him in

the 19th-century zeitgeist of interchangeability. He applied this

expertise to the nascent motor industry as early as 1870 as a principal

in the machine shop Leland & Faulconer, and later was a

supplier of

engines to Ransom E. Olds's Olds Motor Vehicle Company, later to be

known as Oldsmobile. He also invented the electric barber clippers, and

for a short time produced a unique toy train, the Leland-Detroit

Monorail.

He created the Cadillac automobile, bought out by General Motors. He

also founded Lincoln, later purchased by the Ford Motor Company. |

The Brown and Sharpe factory was

instrumental in inventing or perfecting the tools necessary to make

everything we use today from metal. From automobiles to

spaceships, they all started with Brown and Sharpe when they

invented two main tools: The Universal Milling Machine and

the Universal Grinding Machine. They also perfected the

Universal Screw Machine, for without, little could

be precisely made. All of these inventions were due to the Willcox and

Gibbs sewing machines, and the need to make them faster and better.

Today:

Rexel, the world's largest distributor of electrical parts, bought a

controlling interest in Willcox & Gibbs, and since

Rexel was not interested in serving the apparel industry, it sold this

segment of Willcox & Gibbs's business to WG, Inc. for about $44

million in cash, stock, and warrants and moved the company's

headquarters from Manhattan's garment district to Coral Gables,

Florida. In 1995 Rexel, S.A. raised its stake in Willcox &

Gibbs to 44 percent and changed the name of the company to Rexel Inc. |

To read the entire

article, follow these links:

James Gibbs

The Willcox

& Gibbs Company

***The

Battle Of Piedmont***

| Significance: On 5 June 1864, the US army of

General David Hunter crushed the smaller Confederate army at Piedmont,

killing the CS commander (General ``Grumble'' Jones) and taking nearly

1,000 prisoners. Piedmont was an unmitigated disaster for CS arms in

the Valley. The disorganized Confederates could do nothing to delay

Hunter's advance to Staunton, where he was reinforced by Brig. Gen.

George Crook's Army of West Virginia marching from the west. United,

the US forces moved on Lynchburg. Hearing of Jones' defeat, Gen. Robert

E. Lee first rushed J. C. Breckinridge's division back to Rockfish Gap

and then detached the Second Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia

under Lt. Gen. Jubal Early to confront Hunter at Lynchburg. This

detachment severely limited Lee's ability to undertake

defensive-offensive operations on the Richmond-Petersburg lines and

served to open up the Shenandoah Valley as a second front in the 1864

fighting in Virginia. |

Front

Back

Back to Index

|